SATO Oki (hereinafter referred to as Oki) is one of Japan’s leading designers and architects. As the representative of the design office “nendo,” he has worked on a wide range of projects including architecture, interior design, product design, and graphic design. In recent years, he was in charge of the design of the Olympic cauldron for the Tokyo 2020 Olympics, as well as the French high-speed train TGV. Oki produced the “Japan Pavilion” at the Expo. We sat down with him to talk about the pavilion’s theme and unique points.

Click here for the Japan Pavilion’s official website.

— You also worked on the Japan Pavilion at Expo 2015 in Milan. Ten years later, you’ve been appointed General Producer and General Designer of the Japan Pavilion at Expo 2025 Osaka, Kansai, Japan. What are your thoughts on this? Were there any differences you noticed between working overseas and at home?

I’ve been running “nendo” for over 20 years, and up until now I’ve received more work overseas than domestically. So, I’ve always felt like I was working away from home. I’m happy to be able to work “at home” this time, but at the same time I feel a sense of responsibility.

During the Expo in Milan, even after it opened, about half of the site was still under construction. It felt like the pavilions were gradually appearing while the Expo was being held (laughs).

On the other hand, at this Expo in Japan it made the news when only one or two pavilions were still incomplete, and there was a negative reaction… I thought, “So, this is the kind of uproar it causes…” It really brought home the differences between overseas and domestic approaches.

— So, things were completed after the opening then as well. Having experienced things both overseas and in Japan, I’d like to know what you thought about the Japan Pavilion this time.

I’ve been pondering what it means to produce a pavilion for the World Expo amidst the challenges facing the world, including the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic and various conflict. The theme of Expo 2025 Osaka, Kansai, Japan is “Designing Future Society for Our Lives,” which aims to create a sustainable society where each individual can decide how they want to live and maximize their potential, with the international community working together to create that society.

However, in a world overflowing with information and changing at an accelerating pace, the role of the Expo is also at a major turning point. The latest news is available online, and people can travel anywhere they want. It’s only natural that some people will question the point of gathering together for an Expo. Simply showcasing something new, unique, or future-oriented, as in the past, is unlikely to resonate.

— What were some of the key points you focused on when producing the Japan Pavilion?。

I often pay attention to the “tiniest details,” not just in large-scale projects like this one, but in general as well. Even down to the smallest details that no one would notice.

I’ve designed small ballpoint pens and gum packaging in the past, but even though this project was larger, I was conscious of not making it too general. For example, for the part of the pavilion where light dances along the walls, what is the best speed, or what colour and size each letter should be to make it look natural?

I was also very conscious of making sure that these meticulously crafted individual elements didn’t feel disjointed but linked together. I wanted to create points in each exhibit that would make people think, “Oh, so this bit and that bit were connected,” making it enjoyable not just once, but every time you visit.

— Regarding attention to detail, was the fine-tuning process particularly challenging when you were working with so many different specialists? What aspects did you focus your efforts on?

Broadly speaking, there are two main approaches. Traditionally, the design process starts with the “box” i.e. the building, but this time we started with the overarching story that we wanted to tell. We needed a “protagonist” for this story, and we settled on waste from the Expo site, envisioning a narrative that follows it from beginning to end. Naturally, any changes to the story would alter the form of the box, interior, and installations. You might think that with such a large box, doing that would be an endless task, but we just went for it and found a way to make it work within the budget and schedule.

Also, in bringing this story to life, we were conscious to avoid creating strict vertical divisions within the organisation as much as possible. Instead of thinking in terms of “this is my part” and “this is your part,” the design team, architecture team, and interior team all participated in meetings to discuss how we could achieve our vision. It was like everyone crowding around a single ball in elementary school soccer (laughs). It may look clumsy at first glance, but we tried not to draw boundaries, so we were able to all share our opinions and work together on every part.

— Listening to you talk, it sounds like it would be a very time-consuming method, so why did you decide to go with it that way?

The main reason was that we placed importance on the “story”. But I also felt that Japanese architecture, for better or worse, has become rather stagnant, with cityscapes growing increasingly similar. If the construction process is the same, you inevitably end up with similar results. That’s why, for the Expo, I wanted to employ methods we’d never used before. While this process might not be perfect either, I’d be delighted if we could carry forward that process even after the Expo concludes as a new challenge.

— We’ve talked about the relationship between the building and the story, but there are messages written throughout the Japan Pavilion. Do you think reading them helps unravel the story you’re trying to tell?

While the messages undoubtedly help express the story, the first thing I asked copywriter WATANABE Junpei to do was to write them in “middle school-level language.” Rather than making definitive statements like, “This is how it is!”, I asked him to communicate things in a softer, more ambiguous way. I don’t want to directly present the “answer” through words or exhibits. I want to offer hints and opportunities, like, “how about this?” I want visitors to go home and search for the answer themselves. So, while there are messages in key places around the pavilion, we tried to keep the amount of text minimal.

— I see, so leaving it up to the viewer is also part of design. In that context, could you give us some hints about how you came up with the theme of Expo 2025 Osaka, Kansai, Japan “Designing a Future Society for Our Lives,” and the theme of the Japan Pavilion, “Between Lives”?

Going back for a moment, I’ve always felt that it would be a little strange to present concepts like “life” or “the future” as they are. In this world, even if the mood of the times says, “Isn’t life brilliant?” I wonder if everyone can relate to that.

Japan’s period of high economic growth has passed, and the economy and society don’t always grow smoothly. There are times when we need to be aware of and accept decline. Besides, people cannot avoid death and aging, right? I thought that what happens after we accept these things is what’s important. Every life inevitably comes to an end. But death isn’t all negative; knowledge is passed on, we become nutrients for plants and animals, and there are always connections and cycles between us and the next life. Whether we are aware of that process or not. I thought that if people could see that, they would be able to feel the beauty of life. But having said that, it would be grotesque to show a corpse as it is. That’s why the main character became “garbage.” If you think of yourself and the garbage as just one small part of the circle of life, then we’re not that different.

— You’re right. Rather than simply saying, “Life is wonderful,” I think there’s something more redemptive about the image of everything being connected and circulating. Not only does the entire Japan Pavilion express this idea, but there are also many installations that give it that feeling.

That’s exactly right. Like how waste decomposes into energy and new materials, or how algae have the power to nurture new life. This “never-ending cycle” has the power to realise a sustainable society, but it also has the power to make us think positively about life, not just its birth but also its disappearance.

Take for example the installation in the “Factory Area,” where water falls on diatomaceous earth, creating patterns that disappear as it makes one revolution. I think the Japanese culture of finding beauty in the falling cherry blossoms and the fading of sparklers is also a way of looking at decline in a positive light.

And it’s precisely because these things are so ingrained in Japanese sensibilities that we don’t usually think about them much. So, I think it’s wonderful to look at them again and notice them. To put it in perspective, it’s fun to buy something new, but it’s also like the joy of suddenly finding something you’ve lost. I thought it would be great if we could express that kind of feeling in the Japan Pavilion. If there are people who, upon hearing the name “Japan Pavilion,” think, “I already know about Japan…”, then I would like those people to visit.

— The Japan Pavilion deals with deep themes, but the inclusion of many Japanese characters is both surprising and entertaining. Like Hello Kitty dressed as algae!

This concept was around from the early stages, and I wanted to communicate it effectively through something non-verbal. Characters are a wonderful product of Japan. Since there are exactly three areas, I thought it would be easy to understand if characters represented them.

The Plant Area generates energy from waste, and its chemical components combine and transform, which is a perfect fit for the nature of BE@RBRICK. The Factory Area featured Doraemon, who wields a variety of items. In the Farm Area, Hello Kitty, who can dress up in many different ways, was a perfect fit for showcasing 32 types of algae.

— Each area has its own unique exhibit, so it’s never boring. Is there any area in particular that you’d like visitors to pay attention to?

One thing all three areas have in common is that they always have an open “space” at the end.

I particularly like the water basin in the plant area. It’s surrounded by CLT*1, with only water and sky as the only thing visible. I’ve made a lot of different things, but I think manmade structures can’t compete with nature. The impression changes with the weather and time of day, and the atmosphere flows. Looking at the next Mars rock*2, I think you can also feel a connection to the future.

*1 Cross-laminated timber. Made with domestic cedar.

*2 “Mars rock” contains clay minerals that are thought to only form in the presence of water, making it deeply connected to water.

The water basin is located in the centre of the Japan Pavilion. Placing something in the centre would make it the main focus, so I decided from the beginning not to place anything there. I wanted the perimeter to be the focus.

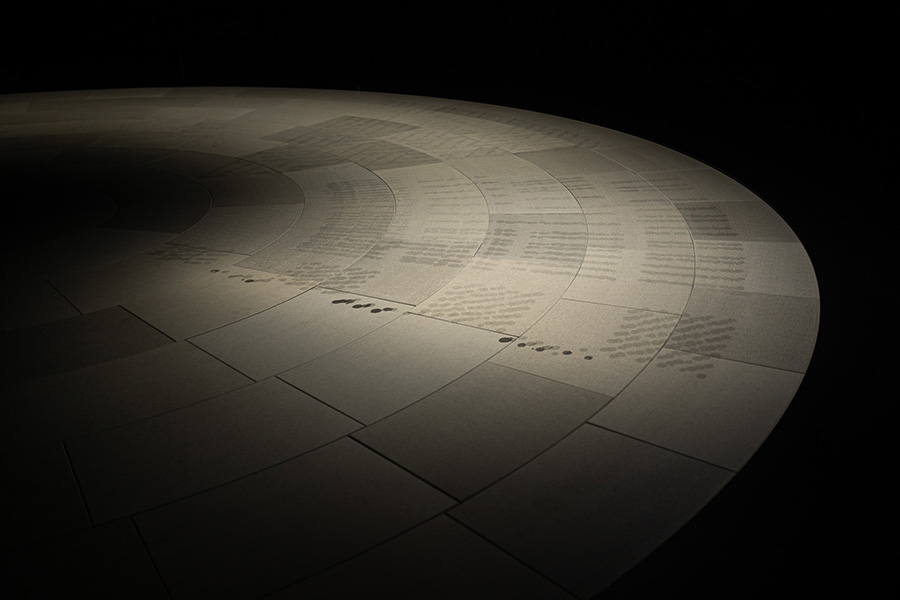

The “space” of the factory area is the diatomaceous earth disk. Diatomaceous earth is a fossilized algae. Water droplets soak into it, creating fleeting art that disappears… I hoped to convey the Japanese value of appreciating the ephemeral. Initially, we discussed how to eliminate the clicking sound of the dropper when it drips water, but ultimately, we decided it might be more interesting to expand on that sound and came up with a thumping sound reminiscent of a Japanese drum. The expression of water movement, graphics, movies, and musical instrumental expression. I used ways of thinking I’d never used before. Incidentally, we tried out diatomaceous earth from around the world, but Japanese diatomaceous earth proved to be the best. The manufacturer uses the same material for their foot mats.

At the end of the farm area is a space where actual algae are grown. The tubes where algae grow, which cover the entire room, give off a sense of vitality.

Also, and this is something that might not be particularly noticeable, but the music that plays in each area is the same melody, but it’s played on different instruments – marimba, strings, and piano. Be sure to visit and give it a listen.

— Finally, Mr. OKI, you were born in Canada and are active overseas, what makes you think, “This is what’s great about Japan!” or “This is the cycle of Japan?”

When I think of cycles, the first thing that comes to mind is Shikinen Sengu, the tearing down and rebuilding of shinto shrines, which is also featured in the Japan Pavilion. I think this might be easily misunderstood by people overseas. Usually, when we think of sustainability or circularity, we think of creating something, using it for decades, and then regenerating it. But Shikinen Sengu is the opposite idea. It’s not about passing on things, but skills. The 20-year interval at Ise Shrine is the perfect span of time. A newcomer can work three times before finally becoming a master carpenter. Skills are passed down and passed on to the next generation. Materials are also planted and brought from the mountains for this purpose. I think that’s a very Japanese sensibility, a sense of renewal through cycles.

What I find amazing is that, because it’s based on passing on skills and knowledge, there are no blueprints! When we tried to recreate the Shikinen Sengu ceremony at the Japan Pavilion, we found that we couldn’t make a model, so we asked “Doraemon” to introduce it in a comic strip.

— What do you want visitors to feel and take away from their visit to the Japan Pavilion?

Please give a message to the visitors to the Japan Pavilion and to the next generation.

I wonder… saying “take this home with you” would be the answer, so I’d rather not give an answer if possible.

I was born in Canada and came to Japan when I was 11 years old, and what I felt like I had been transported to the “world of Doraemon.” Things like mechanical pencils that dispense their lead when you shake them, erasers that collect eraser dust, and candy lids that seal neatly after opening. Each one of them was a shock to me, and it made me think that Japan and its innovations are wonderful. The things that Japanese people take for granted are cool. Similarly, the value of appreciating the things that circulate in nature, which has been normal in Japan since ancient times, is also cool. Garbage, dead insects, withered flowers… these are not things that are finished or dirty, but part of the “circle of life” that we are part of. If you come to the Japan Pavilion and feel something like that, I think it might change the way you see the world.